As the founder of progressive education, Dewey radically changed the approach to learning through experience and critical thinking, established experimental schools, and fostered the development of a democratic society. He authored over 1,000 works, including Democracy and Education, Experience and Education, and How We Think. Read on newyork1.one for more about his life and the ideas on education and democracy that shaped the modern American school system and continue to influence pedagogy worldwide.

Social Roots of John Dewey’s Development

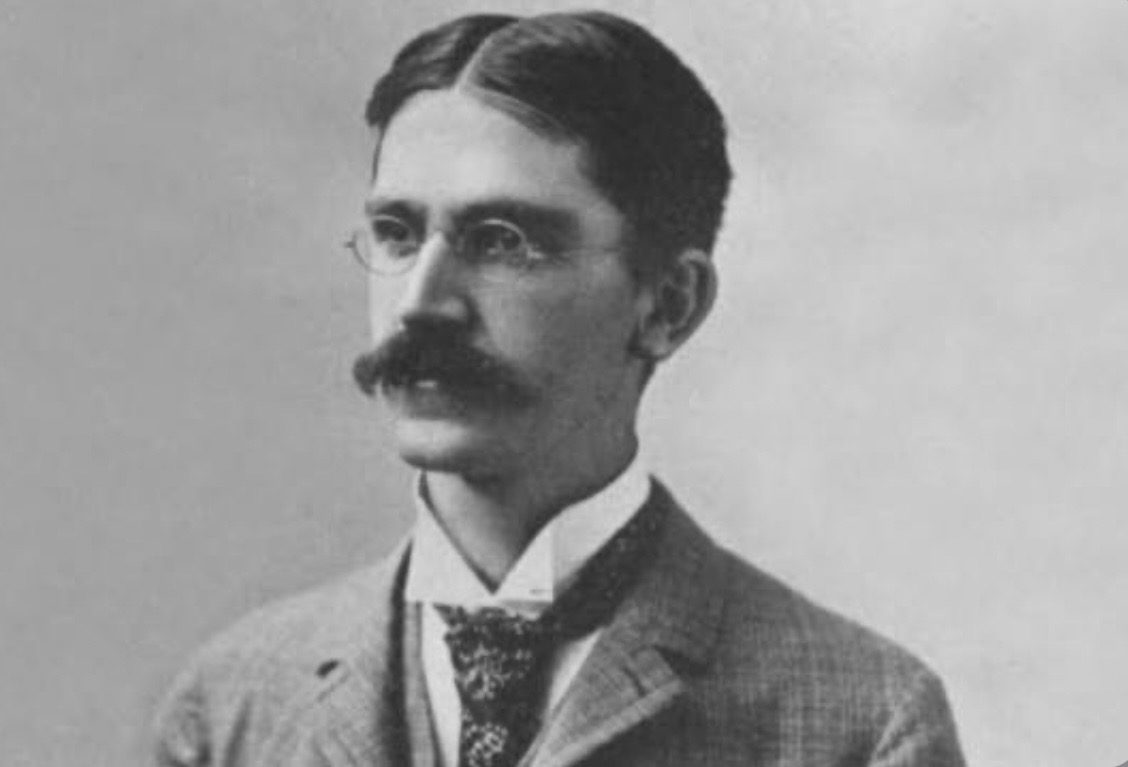

John Dewey was born on October 20, 1859, in Burlington, Vermont, to Archibald Sprague Dewey and Lucina Artemisia Rich. The family lived modestly but held strong moral and intellectual foundations. John was the third of four sons. His home environment significantly influenced the future philosopher. His mother, the daughter of a wealthy farmer, was a deeply religious Calvinist, while his father, a merchant and book lover, instilled in his sons a love for British literature. During the Civil War, Archibald Dewey left his business to join the Union Army, and after returning from the front, he managed to establish a successful business, providing the family with a stable and comfortable life.

John attended public schools in Burlington and quickly proved to be a capable and inquisitive student. At fifteen, he entered the University of Vermont, where he developed a particular passion for philosophy. Professor Henry Augustus Pearson Torrey played a crucial role in his intellectual formation—a mentor with whom Dewey continued private study even after graduation.

In 1879, John Dewey graduated second in his class from the University of Vermont, was inducted into the Phi Beta Kappa society, and took his first confident steps on the path that would eventually lead him to the status of one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century.

From the Classroom to World Philosophy

John Dewey’s professional journey began not in university departments but in school classrooms. Several years of teaching in Pennsylvania and Vermont convinced him that the traditional school system was fundamentally flawed. It was this disappointment with education and doubts about his own vocation that pushed Dewey to delve deeply into philosophy and psychology.

He famously said:

“Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.”

Following a period of intensive self-study and discussions with his mentor Henry Torrey, he enrolled at Johns Hopkins University, where he was influenced by the era’s leading thinkers, earning his Ph.D. in 1884. That same year, Dewey began teaching at the University of Michigan.

The real breakthrough occurred in Chicago between 1894 and 1904. After heading the Philosophy Department and the School of Education, Dewey developed his own version of pragmatism and founded the Laboratory Schools—a radical experiment in learning through activity. It was here that the ideas articulated in his book The School and Society, which transformed educational thought, were born.

Following a conflict with the administration, John Dewey moved to Columbia University, where he taught philosophy until 1930 and became the central figure in American pedagogy. His influence extended far beyond New York lecture halls: Dewey led professional associations, was active in the teachers’ union movement, and shaped the thinking of future psychologists and educators.

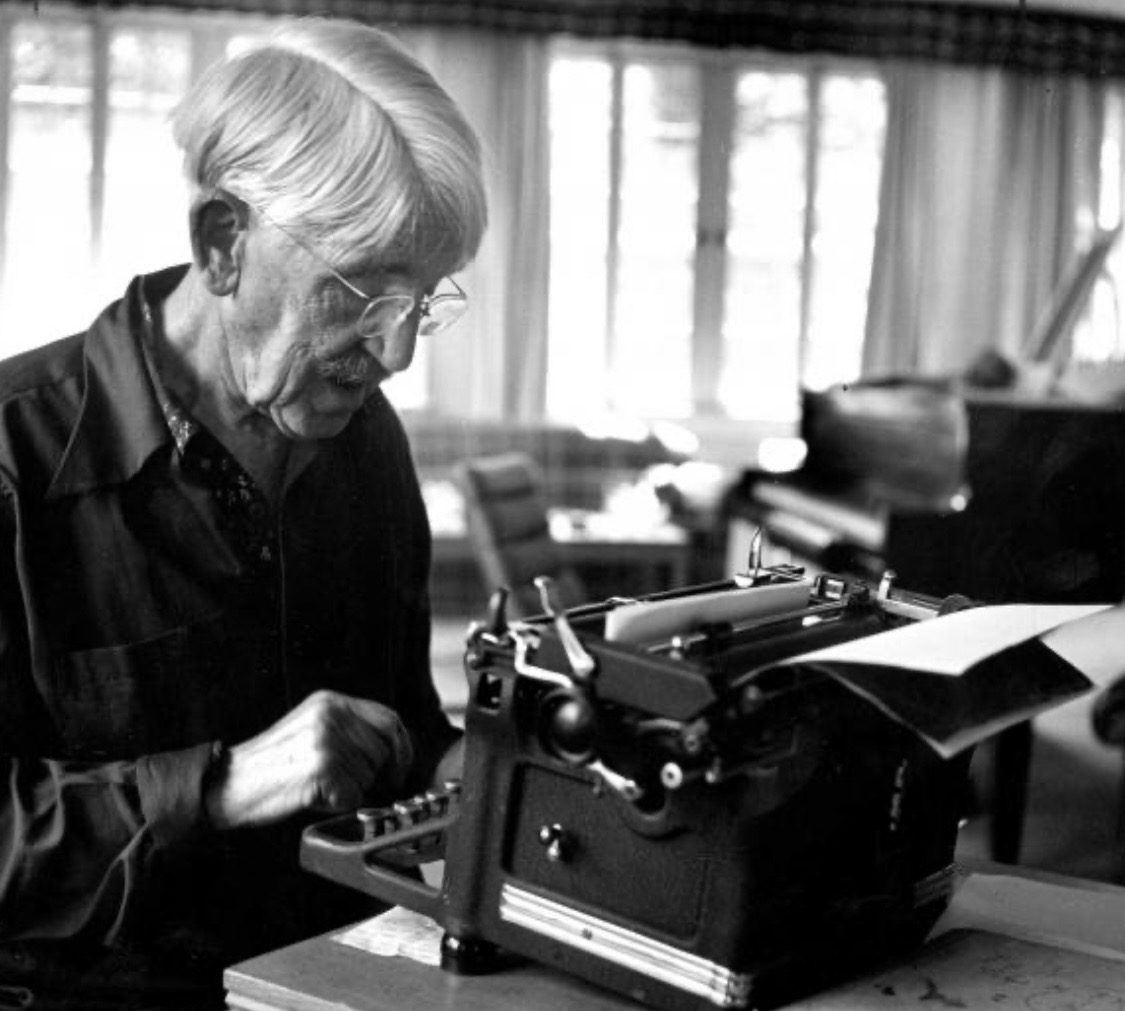

During his lifetime, he published approximately 40 books and over 700 articles. At the core of this legacy lies the idea of experience, action, and democracy as shared responsibility.

Even after retirement, Dewey remained active: he co-founded The New School for Social Research, traveled the world, and advocated for academic freedom. His legacy is not just texts but a living tradition of thought where education is seen as a form of active participation in democratic life.

To Think, To Act, To Change: John Dewey’s Ideas on Humanity and Society

In his early works, written at the University of Michigan, John Dewey laid the groundwork for what would later be called functional psychology. For Dewey, psychology was not a set of abstract diagrams but a way to understand how thinking works in real life—in the interaction between a person and their environment.

Alongside psychology, Dewey developed revolutionary ideas in education. He insisted that learning is a social and active process. School is not a factory for knowledge but a space for living, where a child learns to think, cooperate, and take responsibility. Education, in his view, should not prepare for a distant future life but provide the tools for a fulfilling life here and now.

Dewey paid particular attention to the role of the teacher. For him, a true educator is not a mechanical implementer of methods but a thinking, curious person capable of empathizing with the intellectual inquiries of their students. A teacher’s professionalism is defined not only by knowledge but by character, internal resilience, and a love for learning as a continuous process. Another famous Dewey quote:

“To impose a uniform and general method upon a class of students is to make for mediocrity in all save the exceptional.”

Dewey’s interests also extended far beyond the school. In his works on democracy and journalism, Dewey argued that democracy is not merely a political system but a way of shared life. A public emerges where people recognize common problems and collectively seek solutions. In this model, journalism must not just transmit news but foster dialogue, understanding of consequences, and collective thought.

In aesthetics, particularly in the book Art as Experience, Dewey broke down the barrier between art and everyday life. For him, art is a form of intense human experience, rooted in culture and community, not the exclusive privilege of museums.

Ultimately, John Dewey’s philosophy emerges as a holistic vision of the human being: thinking, active, and social. Psychology, education, democracy, art, and communication converge in his work into a single project—the project of a society that learns through experience and is capable of consciously changing itself.

Social Responsibility and Democracy in John Dewey’s Practice

John Dewey’s social and political beliefs were never separate from his philosophy. This was particularly evident during his time at the University of Chicago when the country was shaken by the Pullman Strike of 1894. Dewey closely followed the events and sharply criticized the position of the upper classes and the press, which depicted the strike leaders as criminals. In private letters, he bitterly noted that even universities, including the University of Chicago, were part of a capitalistic system detached from the real needs of society.

During World War I, Dewey adopted a pro-war stance, believing U.S. participation was necessary to protect democratic values. This move drew sharp criticism, notably from his former student Randolph Bourne, who accused Dewey of allowing his pragmatism to become a tool for justifying the war. Despite this, Dewey did not abandon his active civic position and continued to insist on the synthesis of intellectual freedom and social responsibility.

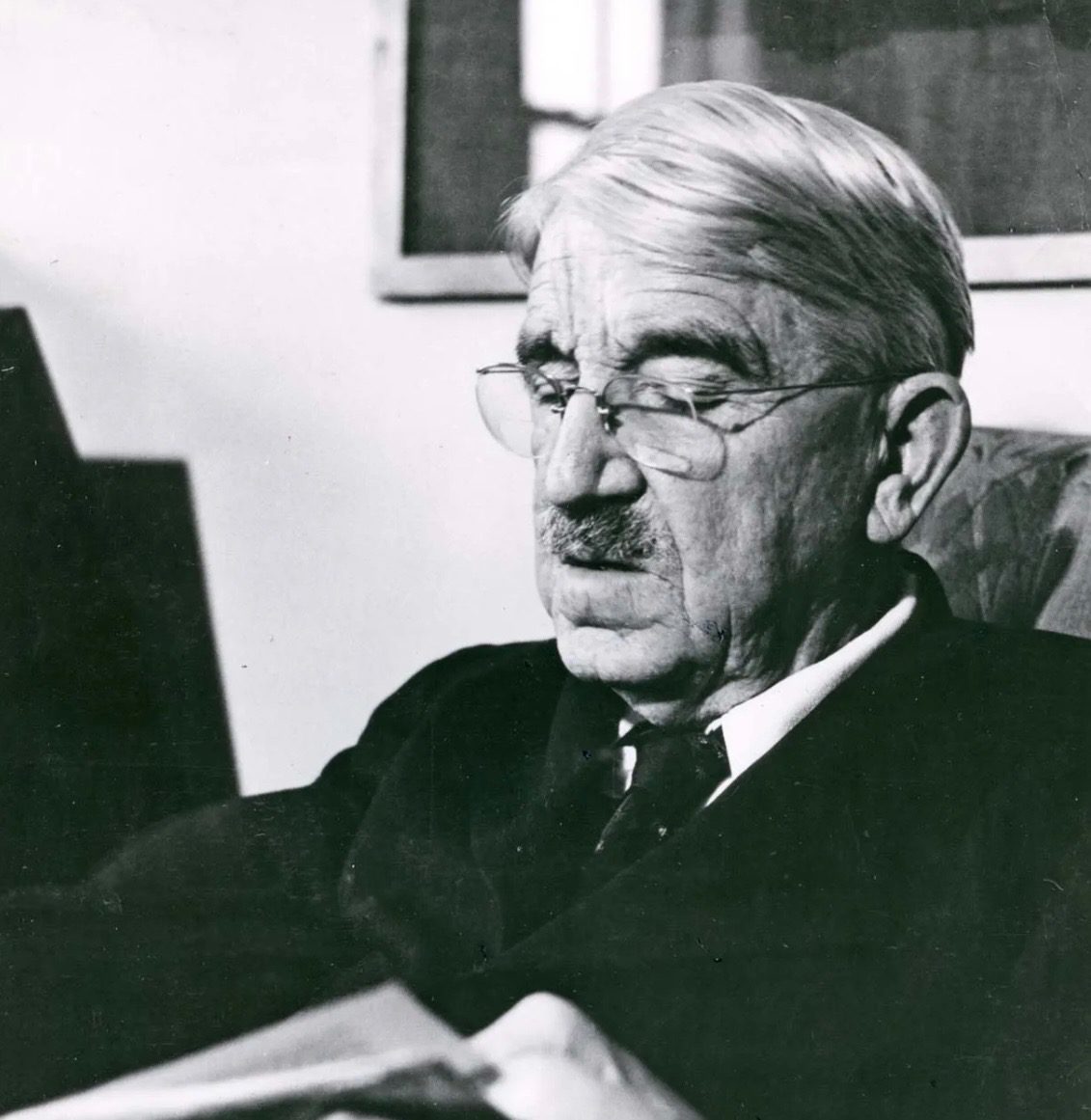

As a consistent advocate for academic freedom, in the 1930s, Dewey helped found the International League for Academic Freedom alongside Albert Einstein. Simultaneously, Dewey supported movements for women’s rights, teacher autonomy, and racial equality, collaborating with organizations that later became part of the NAACP.

In the late 1930s, Dewey chaired the League for Industrial Democracy, which educated students about the labor movement. He was also a strong proponent of Henry George’s ideas on land value taxation, viewing them as fundamental to socially responsible thinking. For Dewey, politics was not reduced to party struggle: he criticized American democracy for its dependence on big business and even attempted to facilitate the creation of a new People’s Party that would represent the interests of ordinary citizens.

Dewey remained an active thinker until the end of his life, maintaining a wide network of intellectual contacts and writing on politics, culture, education, and science. He died in New York in 1952, leaving behind the legacy of a philosopher for whom democracy was not an abstract idea but a daily practice of shared responsibilityfor society’s future.