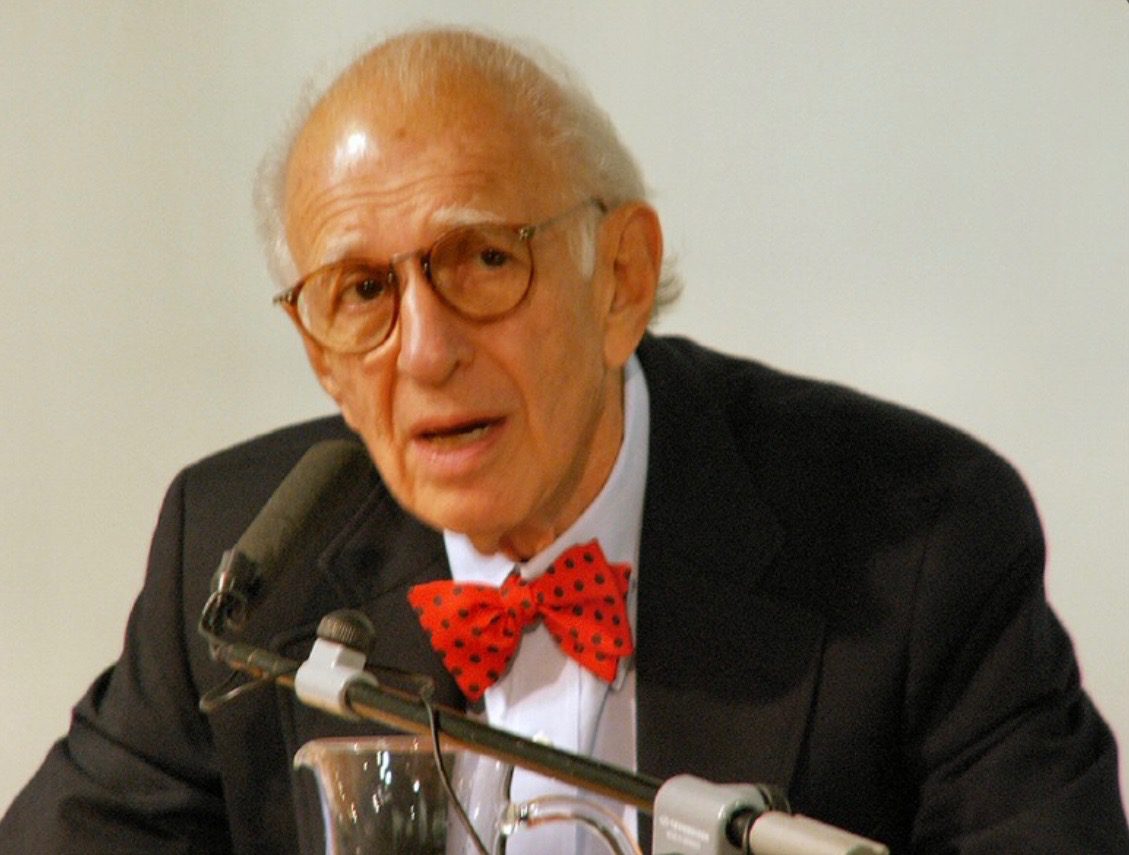

Eric Kandel is an American neurobiologist and psychiatrist, a Nobel laureate, and a Professor Emeritus at Columbia University, renowned for his groundbreaking discoveries regarding the molecular mechanisms of memory. He is the author of influential books such as In Search of Memory and Principles of Neural Science. Read on newyork1.one how Kandel bridged the gap between psychology, neurobiology, and molecular science, laying the foundation for our modern understanding of the human brain.

A Childhood Shattered by History

The story of Eric Kandel begins long before his scientific career—in the complex and vibrant world of pre-war Central Europe. His mother, Charlotte Simels, came from an educated Jewish family in Kolomyia (then part of Austria-Hungary). His father, Hermann Kandel, grew up in a modest family in Olesko, near Lviv. Both moved to Vienna as young adults, where they met, married in 1923, and attempted to build a quiet middle-class life. On November 7, 1929, their son Eric was born.

His father owned a toy shop. The family was fully integrated into Austrian society, deeply in love with the city’s culture, music, language, and intellectual atmosphere. Yet, beneath this refinement lay a dark reality: chronic antisemitism that grew more aggressive with each passing year.

Following the annexation (Anschluss) of Austria in March 1938, Jewish life was violently upended. Beatings, humiliations, and the confiscation of property became commonplace. During Kristallnacht, Eric’s father was arrested, the family was evicted from their apartment, and the toy shop was looted. For a nine-year-old boy, this was a formative encounter with systemic violence—an experience etched into his memory for a lifetime.

Realizing it was no longer safe to stay, his parents made the agonizing decision to flee. In 1939, Eric and his older brother were the first to leave Europe, sailing from Antwerp to the United States. Their parents eventually joined them—just days before the outbreak of World War II.

In Brooklyn, they started over from scratch. His father initially worked in a toothbrush factory before eventually opening a small clothing store. This shop became the family business and the financial pillar that allowed the children to pursue an education. Kandel attended a yeshiva and later the prestigious Erasmus Hall High School. Interestingly, his path to science did not start with biology, but with history and literature. At Harvard, he studied the intellectual responsibility of German writers during the Nazi era. Gradually, however, his interest in human behavior, motivation, and trauma led him toward psychology, psychoanalysis, and ultimately, neurobiology.

His experiences in Vienna became more than a personal tragedy; they were an intellectual challenge. How could a cultured society descend so rapidly into barbarism? Why do traumatic events sear themselves into memory with such intensity? These childhood flashes of memory would later lead him to discoveries that redefined our understanding of how memory works and how experience physically shapes the brain.

From Psychoanalysis to Neuroscience

In those days, becoming a psychoanalyst required medical training. Almost impulsively, Kandel chose New York University Medical School, enrolling in 1952. While his initial goal was psychiatry, he became increasingly fascinated by the biological basis of mental processes. In the mid-1950s, this was a radical perspective—most psychoanalysts preferred to keep the mind separate from the physiology of the brain.

Kandel took a decisive step toward neuroscience during an internship in Harry Grundfest’s laboratory at Columbia University. There, he immersed himself in the electrophysiology of neurons and first encountered the limitations of studying memory within complex brain systems.

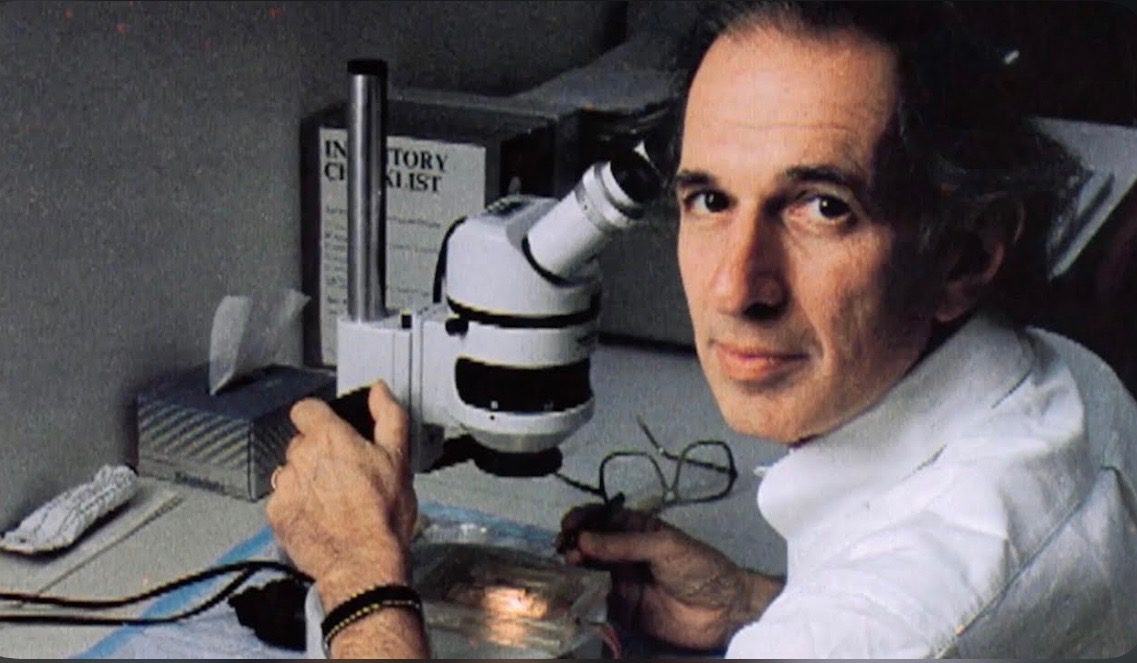

His research on the hippocampus at the National Institutes of Health yielded vital insights but also demonstrated that memory isn’t “hidden” in a single spot; rather, it is formed through changes in synaptic connections. This realization led Kandel to a bold decision: to seek answers not in the human brain, but in simpler organisms. Despite the skepticism of many colleagues, Kandel chose the Aplysia (a giant sea slug) as his model. Its nervous system allowed him to literally see how learning changes synapses.

In 1962, he traveled to Paris to master this model. Within a few years, he published results that laid the cornerstone of modern memory science. For the first time, scientists could study memory at a molecular level rather than just theoretically. Kandel’s collaboration with biochemist James Schwartz revealed fundamental truths: short-term memory occurs without the creation of new proteins, whereas long-term memory requires protein synthesis. They also discovered that short-term changes in the brain are triggered by chemical signals within neurons. These findings proved that experience literally changes the brain on a physical level.

Memory Research at Columbia University

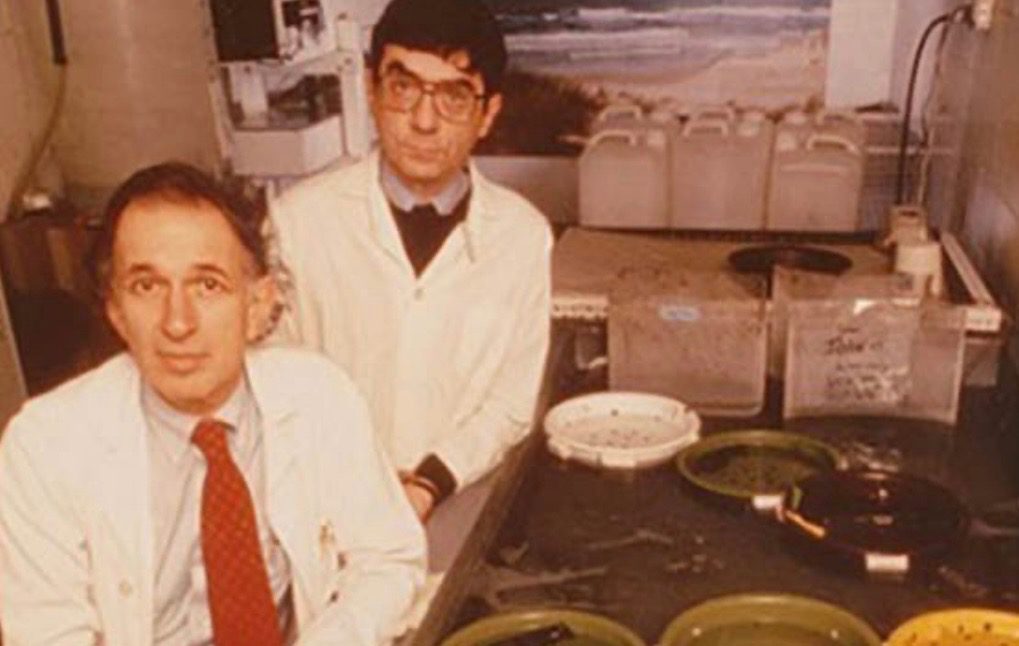

In 1974, Eric Kandel moved to Columbia University, where he became the founding director of the Center for Neurobiology and Behavior. Alongside his colleagues, he built a multidisciplinary team dedicated to uncovering the biological foundations of memory.

By the 1980s, Kandel had become a senior investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, helping to establish a world-class center for molecular neuroscience at Columbia. This allowed him to merge neurophysiology with the cutting-edge tools of molecular biology and recombinant DNA, vastly expanding the scope of memory research.

In the 1990s, Kandel returned his focus to the hippocampus, this time utilizing genetically modified mice. He discovered that the same chemical signals inside brain cells he had first identified in the simple sea slug Aplysia were also essential for memory in mammals. These signals help neurons strengthen their connections to one another, effectively “locking in” information about space and experience.

While studying “place cells” in the hippocampus, Kandel demonstrated how the brain constructs an internal map of the surrounding world. He found that this map is only stored long-term when an individual focuses their attention, which in turn triggers the production of new proteins in the neurons. Through this work, memory evolved from a vague psychological concept into a phenomenon with a clear, biological explanation.

The Nobel Prize, Legacy, and Reconciliation with Vienna

When Eric Kandel was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2000, European media outlets were quick to label him an “Austrian laureate.” For Kandel, this felt both painful and hollow. He wryly noted that the reaction was “typically Viennese”—convenient and not entirely sincere. He made his stance clear:

“It was a Jewish-American Nobel Prize, not an Austrian one.”

After all, it was Vienna that had driven him into exile during the Nazi era.

Shortly after the announcement, Austrian President Thomas Klestil called Kandel with a direct question:

“What can we do to make this right?”

Kandel’s response was both specific and principled. First, he insisted on renaming the Dr.-Karl-Lueger-Ring—a major street named after the antisemitic mayor of Vienna whom Hitler had famously cited. Second, he called for the restoration of the city’s Jewish intellectual tradition through scholarships for Jewish students and researchers, alongside an honest, public conversation about Austria’s role in the Holocaust.

These steps marked the beginning of a slow reconciliation. Eventually, Kandel accepted honorary citizenship of Vienna and re-engaged with the cultural and academic life of the city that held both his trauma and his heritage. This “homecoming” was symbolized by his 2012 book, The Age of Insight—a sweeping historical and scientific journey from 1900s Vienna to the present day.

Beyond memory research, Kandel made vital contributions to the study of neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders, specifically Alzheimer’s and schizophrenia. He was also instrumental in helping the medical community distinguish between normal, age-related forgetfulness and pathological memory impairment.

Eric Kandel is globally recognized as the lead author of the definitive textbook Principles of Neural Science, which serves as the foundation for neuroscience education worldwide. He has frequently emphasized that for him, science is a source of joy rather than just professional acclaim, famously proving that “there is life after the Nobel Prize.”

His life is more than a triumph of the laboratory; it is a testament to how memory, accountability, and dialogue can reshape both cities and cultures.