In the past, it was one of the largest in the world and personified Brooklyn’s industrial might. At its peak, the factory processed about 4 million pounds of sugar daily, supplying the country with sweetness. In the 21st century, the restored building has gained new life—the historic structure has been transformed into a modern office and residential complex, The Refinery at Domino, which preserves the architectural legacy of the past. Read on newyork1.one for this New York sugar story.

A Sweet Empire on the East River Shore

In Williamsburg, Brooklyn, stands a majestic red building—the former Domino Sugar Refinery plant, which was once the heart of the Havemeyer sugar empire and a symbol of New York’s 19th-century industrial power.

The history of this place began in 1807 when two German immigrants, Frederick Havemeyer and William Havemeyer, opened a small sugar refinery on Vandam Street in Manhattan. Their business quickly grew; by the middle of the century, the family firm had become one of the main sugar producers in the country. However, Manhattan soon became too small, and the entrepreneurial heirs decided to move production to the then-young neighborhood of Williamsburg.

In 1856, the founder’s nephew, John Havemeyer, opened a new factory here, which eventually became known as Havemeyers & Elder or the “Yellow Sugar House.” This marked the beginning of the rapid growth of Brooklyn’s sugar industry. By the 1870s, the Williamsburg area had become the world’s largest center for sugar processing, providing the majority of the sweet product for all of America.

The factory’s location was ideal. Thanks to the depth of the East River, ships carrying cane sugar from the Caribbean and South America could dock right next to the production buildings. However, the refinery’s fate was not always sweet. In January 1882, a devastating fire destroyed almost the entire complex between South 3rd and 4th Streets. Over 2,000 workers lost their jobs, and damages amounted to $1.5 million—a huge sum for the time. But the Havemeyers did not give up. The very next year, they rebuilt the factory—this time out of brick, with a fireproof structure designed by Theodore Havemeyer and Thomas Winslow.

The new factory was striking in scale. Its filter towers and smokestacks dominated the Brooklyn industrial landscape until 2004, when production finally ceased.

How Sugar Was Made at Domino Sugar

The production process at Domino Sugar was complex and almost alchemical. Cane sugar from over forty countries was delivered by ship. It was unloaded, mixed with water, and lifted through pipes to the upper floors of the factory.

There, in gigantic kettles, the syrup was purified through layers of cloth and a filter made of charred bone, which gave the sugar its white color. The solution was then boiled in vacuum pans over 30 feet tall, molasses was separated in centrifuges, and the sparkling crystals were dried, roasted, and sorted by size.

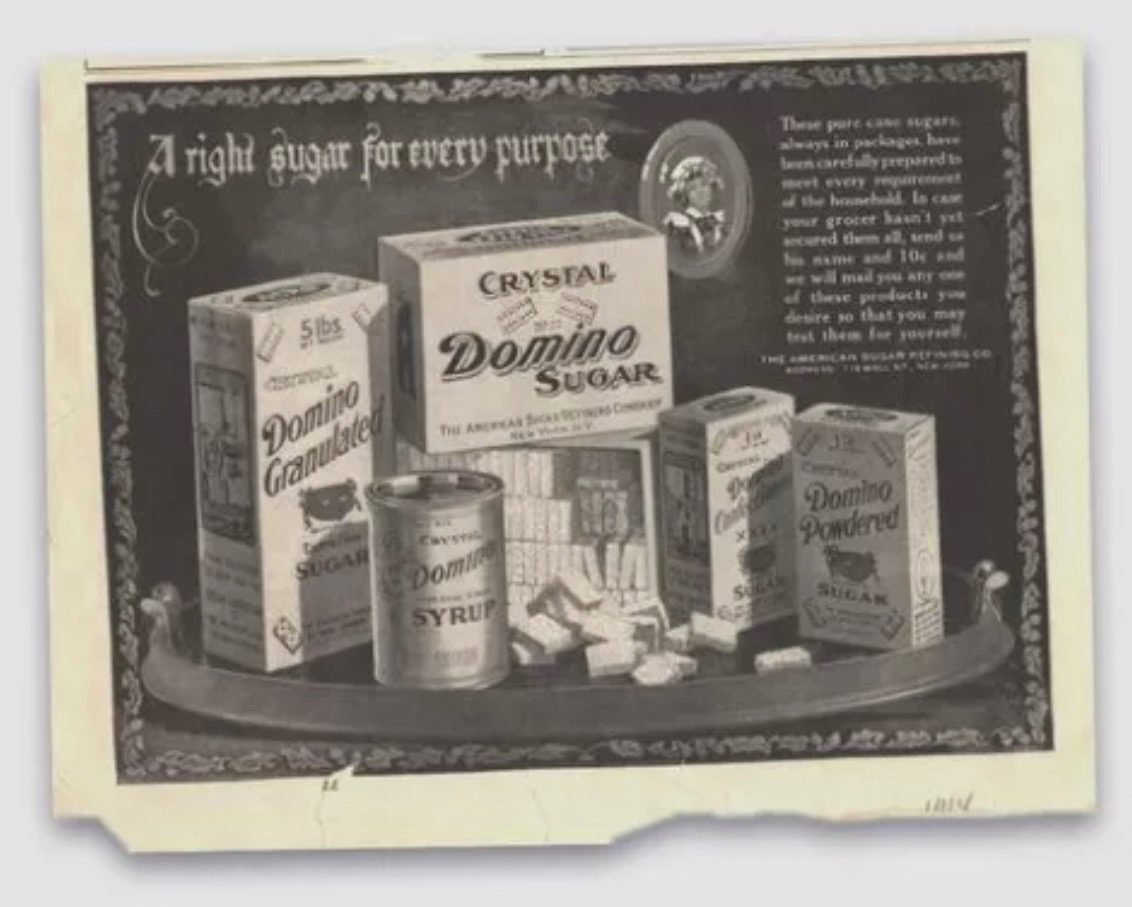

The final stage resembled a factory of sweet treasures: cubes, sugar tablets, and syrups rolled off the production lines—everything that would later grace the shelves of American stores. The product was packed into wooden barrels and sent to warehouses or customers across the country.

Behind this sweet product lay the arduous labor of thousands of people. The workday at the factory lasted at least ten hours, the temperature in the workshops reached unbearable heat, and the wages were quite modest: from $1.12 to $1.50 per day (equivalent to about $40–$55 in modern prices).

Initially, most workers were German and Irish immigrants, followed later by those from Southern, Eastern, and Northern Europe, as well as the West Indies. They lived in cramped boarding houses near the factory or commuted by streetcar from other neighborhoods. The enterprise’s basement had lockers and showers, but the workers often joked that “the sugar here glitters more than the people.”

Despite the harsh conditions, many stayed at Domino for years; the average tenure exceeded eight years. In the early 20th century, the company gradually raised wages, and some workers even began receiving pensions—an unheard-of benefit at the time. By 1920, about 10% of the factory workers were women, a significant step for the industry during that period.

Domino Sugar in the 20th Century

By 1900, the factory was processing half of the nation’s sugar. The gleaming Domino letters, crowned with a star over the i, rose above the rooftops of Brooklyn, becoming one of the city’s most recognizable symbols. In 1907, the company built its own railway—the East River Terminal—to connect the factory to the port. The complex grew so large that it occupied a quarter mile along the waterfront. In the 1920s, 4,500 people worked here. The sugar empire felt so secure that it didn’t even insure its buildings:

“Our factory doesn’t burn,” the executives said.

But life quickly proved them wrong. In 1917, a powerful explosion during World War I tore apart one of the production buildings. Initially, sabotage was suspected, as Germany was at war with the U.S., but it was later found that the cause was a spark that ignited sugar dust in the engine room.

The factory endured, however. Within two years, life returned to its usual rhythm—the clang of metal, the hum of the kettles, and the aroma of melted sugar.

In 1926, the factory underwent a major reconstruction: a new boiler house, a massive warehouse, and a 500-foot pier were added, where ships from the Caribbean and Cuba docked. Three million dollars were spent on the modernization—an investment that made the production the most efficient in the country. By 1941, Domino was producing ** over sixty types of sugar**. The Brooklyn Citizen newspaper wrote:

“Brooklyn is sugar, just as Detroit is automobiles and Pittsburgh is steel.”

Over three decades, the factory paid $156 million in wages, welcomed over two thousand ships, burned millions of tons of coal, all for the white crystals without which no American kitchen could function.

But the world was changing. After World War II, production began to decline. Some operations were moved to Baltimore, leaving only a shadow of the former power in Brooklyn. In the 1950s, the number of workers decreased by two-thirds, though the company still invested in modernization.

In 1970, it was renamed Amstar; in 1988, it was bought by the British corporation Tate & Lyle, and three years later, the Domino Sugar brand returned to the packaging. But the former scale was gone; by the 1990s, only four hundred workers remained.

When the owners announced layoffs in 1999, 284 workers went on strike. It lasted twenty months—one of the longest in New York history. People stood at the gates even in winter, holding signs that read, “Sugar is people.”

When the strike ended in 2001, the plant was acquired by American Sugar Refining.

The Transformation of the Legendary Factory

In 2003, American Sugar Refining announced the closure of the plant. In January 2004, all employees lost their jobs. As researcher Raphaelsson said, “for the workers, this place was almost a utopia—they had good conditions, decent pay, a sense of security.” But after the closure, that utopia dissolved. One former worker bitterly confessed to The New York Times:

“Last week, I found out I’m a dinosaur. Working in one place used to mean reliability, but now it means obsolescence.”

Another worker, ten years later, recounted how many of his colleagues fell into depression, became alcoholics, and saw their families break up after losing their jobs.

However, the decline was not the end of the story. By the mid-2000s, the factory site had become the stage for a new life. In 2004, it was purchased by CPC Resources along with developer Isaac Katan, who planned to build residential and office towers, schools, and parks. Three years later, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission granted landmark status to the most valuable buildings of the complex—the Filter, Boiler, and Finishing Houses.

In 2012, the site was bought by Two Trees Management, which proposed a more open and harmonious project designed by SHoP Architects. The new plan included more green spaces, public areas, and mixed-use development—apartments, offices, cafes, and parks. In 2014, the $1.5 billion project was approved. Phased construction began: the residential buildings 325 Kent Avenue (2017) and 260 Kent Avenue (2018) were erected, and Domino Park opened—a picturesque park along the waterfront that still preserves the scent of the sugar history.

In 2023, the historic Refinery Building finally opened its doors after a massive renovation. Its barrel-vaulted roof was restored, and the famous Domino Sugar neon sign shines again over the East River, albeit in a modern LED version. The area now includes parks and the towers One South First and Ten Grand, and since 2024, the elegant One Domino Square, where a portion of the apartments were sold in the first months.

Today, the Domino Sugar Refinery site is more than just a residential and office complex; it is a symbol of the rebirth of industrial Brooklyn, where the history of hard labor combines with new forms of life.